- Home

- About

- Exhibits

- The Well-Traveled Potato

- Delicious

- Potatoes 101 and Fun Science and Art Projects for All Ages

- Potato Fun: Heads, Puns and Guns

- Cinematic and Musical Potatoes

- Surprising

- Praiseworthy

- Potato People

- Potato Places

- Book Shop

- Wide World of Potatoes: Links

- Contact Us

- Buy The Collection? Set Up TPM in Your Country/Community?

Potato People

Potato historians, scientists and promoters are featured here including authors Redcliffe Salaman, History and Social Influence of the Potato, Lucienne Desnoues, All Potato, Wilhelm Volksen, The Potato in Art and Literature, heirloom potato variety preservationist Donald MacLean, French scientist A. A. Parmentier, American potato scientist and World Food Prize Laureate John Niederhauser and potato art impresario Jeffrey Allen Price.

Potato Promoters

A. A. Parmentier

Parmentier monument in the scientist's hometown of Montdidier, France

Statue of Parmentier at the Faculté de Pharmacie de Paris, bronze par Pierre Hébert

Parmentier Paris Metro station trackside exhibit about the famous potato promoter's career

While serving as an army pharmacist for France in the Seven Years' War, Parmentier was captured by the Prussians, and in prison in Prussia was faced with eating potatoes, known to the French only as hog feed. The potato had been introduced from South America to Europe by the Spaniards at the beginning of the 16th century. It was introduced to the rest of Europe by 1640, but (outside Spain and Ireland) was usually used only for animal feed. King Frederick II of Prussia had required peasants to cultivate the plants under severe penalties and had provided them cuttings. In 1748 the French Parliament had actually forbidden the cultivation of the potato (on the grounds that it was thought to cause leprosy among other things), and this law remained on the books in Parmentier's time, until 1772.

From his return to Paris in 1763 he pursued his pioneering studies in nutritional chemistry. His prison experience came to mind in 1772 when he proposed (in a contest sponsored by the Academy of Besançon) use of the potato as a source of nourishment for dysenteric patients. He won the prize on behalf of the potato in 1773. Thanks largely to Parmentier's efforts, the Paris Faculty of Medicine declared potatoes edible in 1772. Still, resistance continued, and Parmentier was prevented from using his test garden at the Invalides hospital, where he was pharmacist, by the religious community that owned the land, whose complaints resulted in the suppression of Parmentier's post at the Invalides. In 1779 Parmentier was appointed to teach at the Free School of Bakery in order help stabilize Paris' food supply by making bread in a more cost-effiicient fashion. In that same year he published “Manière de faire le pain de pommes de terre, sans mélange de farine”, in which he described how one can make potato bread that still has all the characteristics of wheat bread.

Potato publicity stunts

Parmentier therefore began a series of publicity stunts for which he remains notable today, hosting dinners at which potato dishes featured prominently and guests included luminaries such as Benjamin Franklin and Antoine Lavoisier, giving bouquets of potato blossoms to the King and Queen, and surrounding his potato patch at Sablons with armed guards to suggest valuable goods — then instructing them to accept any and all bribes from civilians and withdrawing them at night so the greedy crowd could "steal" the potatoes. These 54 arpents of impoverished ground near Neuilly, west of Paris, had been allotted him by order of Louis XVI in 1787.

Acceptance of the potato

In 1771 Parmentier won an essay contest in which all the judges voted the potato as the best substitute for regular flour. This was before a time France needed a replacement for wheat, so Parmentier continued to face criticism and lack of acknowledgment for his work. The first step in the acceptance of the potato in French society was a year of bad harvests, 1785, when the scorned potatoes staved off famine in the north of France. In 1789 Parmentier published Treatise on the Culture and Use of the Potato, Sweet Potato, and Jerusalem Artichoke (Traité sur la culture et les usages des Pommes de terre, de la Patate, et du Topinambour), "printed by order of the king", giving royal backing to potato eating, albeit on the eve of the French Revolution, leaving it up to the Republicans to accept it. In 1794 Madame Mérigot published La Cuisinière Républicaine (The [Female] Republican Cook), the first potato cookbook, promoting potatoes as food for the common people. The final step may have been the siege of the first Paris Commune in 1795, during which potatoes were grown on a large scale, even in the Tuileries Gardens, to reduce the famine caused by the siege.

wikipedia.org/wiki/Antoine-Augustin_Parmentier

Dr. John Niederhauser, Potato Scientist and World Food Prize Laureate

John S. Niederhauser, founding member of The Potato Museum's Board of Directors, passed away peacefully at home on August 12, 2005, sleeping in his self-ejecting lounge chair in his study. John would have been amused by this, as it was probably the first time he had been caught sleeping on the job. Though he had retired, his work went on. Once you read this report and visit the links you will know that Dr. Niederhauser packed a lot of work and play into his 88 years. He was rarely idle and seldom quiet.

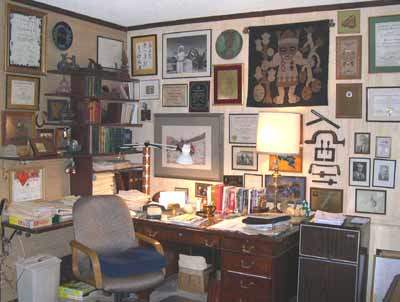

John Niederhauser's home office in Tucson, Arizona. The desk and walls are full of mementoes and awards from a lifetime commitment to helping feed the world.

His World Food Prize is on the shelf just above his chair. It is surrounded by miscellaneous potato memorabilia.

John and his wife, Ann, were early and enthusiastic supporters of The Potato Museum.

"The most important issue confronting the human race

is how we are going to preserve the quality of the environment

and still feed the rapidly growing population into the next millennum.

The Potato Museum provides a vehicle to get the message across."

--J.S. Niederhauser

No brief obituary could possibly do justice to the memory of John Niederhauser, potato scientist.

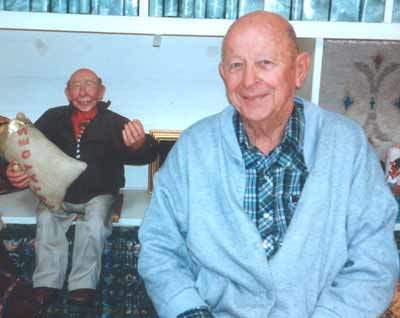

When we last saw him, he was up to his usual hilarious and insightful quips and quirks, discussing politics, world hunger, his beloved Mexico, and, of course, the potato, the vegetable that claimed his attention throughout his long career.

John posing with, well...himself...a popular gift from his family.

There was never a quality shaggy dog story or brief one-liner John did not appreciate, and worse, remember, in full detail. We doubt anyone ever stopped him when he would begin genially," You know the one about the duck and the anti-freeze.......please tell me if you've heard this..." because his story-telling skills were superlative.

A tall man who had been a precocious boy in Central Washington State, and top student at Cornell, earning his PhD in plant pathology in 1943, he went on to be a Rockefeller-funded scientist based in the highlands west of Mexico City. There he determined that the potato strain responsible for late-blight had originated in Mexico where wild varieties had genetic resistance to the pathogen. For 30 years he and his team worked to develop resistant potato varieties that subsistence farmers could grow, thus cutting down on expensive fungicides while also reducing their environmental impact. ( While in Mexico he also found time to become the founder and president of Little League baseball from 1954 to 1969, and the Latin American Commissioner from 1957 to 1969. )

Painting of potato flowers hung on John's bedroom wall.

This potato still life was in the Niederhauser study. Today, thanks to John's family, it is part of The Potato Museum collection.

Not only was potato production hugely increased in Mexico, but programs in Turkey, Bangladesh, India, Colombia and Pakistan were able to boost production four to eight times. John went on to help establish the International Potato Center in Lima, Peru, and several other global agriculture initiatives.

John's wife, Ann Faber Niederhauser, with whom he raised six children, was his companion and support in all endeavors. A gifted weaver not only of rugs and cloth, but also of memorable gatherings of family and friends, Ann died in 2000.

Ann and John Niederhauser

Text copyright The Potato Museum

Here are excerpts from the University of Arizona's statement on the passing of their illustrious professor emeritus.

In Memoriam: John S. Niederhauser, 'Mr. Potato'

By University of Arizona News Services August 22, 2005

Dr. John Niederhauser, internationally renowned potato scientist, 1990 World Food Prize winner, University of Arizona adjunct professor of plant pathology, died Aug. 12, 2005. He was 88.

Niederhauser was a pioneer in international cooperation for the improvement of agricultural productivity worldwide. Known throughout the world as "Mr. Potato" for developing potato varieties resistant to late blight disease, his work has impacted agricultural production in more than 60 countries.

"In 1990, in recognition of his significant contributions to improving the world food supply and alleviating hunger and malnutrition, Niederhauser was awarded the prestigious World Food Prize, the equivalent of the Nobel Prize in agriculture," said Eugene Sander, vice provost and dean of the UA College of Agriculture and Life Sciences. The UA was a major sponsor of Niederhauser's nomination for this honor.

In 1946, Niederhauser joined the newly formed Rockefeller Foundation Mexican Agricultural Program. He spent 15 years working in Mexico on corn, wheat and bean production. During this time, he began to study potato production in Mexico. His work over the next several decades focused on the improvement of potato production in many developing countries.

Due to the success of this work, the International Potato Center, now supported by CGIAR, the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research, was established in Lima, Peru, in 1971. In 1978, Niederhauser established the Regional Cooperative Potato Program (PRECODEPA) in Mexico, Central America and the Caribbean. This cooperative program has grown to include 12 countries. Similar programs have been established throughout the world.

One of Niederhauser's most important scientific contributions was the development of potato varieties with resistance to late blight disease, caused by the fungal pathogen Phytopthora infestans. This pathogen was responsible for many potato disease outbreaks around the world, including the Irish potato famine during the 1840s.

During his research, Niederhauser discovered that the source of the pathogen responsible for the Irish potato famine came from Mexico. More importantly, he discovered many wild inedible potato species in Mexico that possessed a durable field resistance to the late blight fungus. He began breeding work using these resistant lines which resulted in a collection of commercially useful resistant potato varieties. These new varieties allowed subsistence farmers around the world to be able to grow potatoes for the first time with few or no chemical fungicide applications.

Niederhauser's work resulted in the establishment of the potato as the fourth major food crop worldwide. As a result of this work, potato production in Mexico increased from 134,000 metric tons in 1948 to greater than 1 million metric tons by 1982.

In addition to his efforts with potato late blight, one of Niederhauser's greatest contributions was also the large number of scientists and leaders he trained during his career. More than 180 international scientists came and worked with him in his Mexican field plots. He spent considerable time with students as well.

"John was always a pleasure to interact with. His sense of humor, storytelling and compassion about science--and more importantly about all people--made him an irreplaceable treasure," said Leland Pierson, chair of the Division of Plant Pathology.

Niederhauser won numerous awards throughout his career. More recent recognition includes the 1991 American Institute of Biological Sciences Distinguished Scientist Award; the 1996 Medal of Merit by the Ministry of Agricultural Development, Panama; 2001 Honorary Doctor's Degree by the National Agricultural University, Mexico; 2002 Honorary Diploma by the Department of Agriculture, State Government of Mexico; 2002 Honorary Recognition of Outstanding Contribution by the Global Initiative on Late Blight (GILB); 2002 Honorary Doctorate by Oregon State University; and Honoree in 2003 at the 50th Anniversary Meeting of the Inter-American Institute for Cooperation on Agriculture, Costa Rica.

"With John's passing, international agriculture has lost a giant," said Merle H. Jensen, retired associate director of the CALS agricultural experiment station and active chair of the endowment committee. "He was passionate in his concern for students and their ability to further their professional development. His care and concern for Mexico and her people was tireless and his impact will out live all of us."

Jeffrey Allen Price: Potato Art Impresario

Jeffrey Allen Price is the world’s leading potato art entrepreneur and a promoter of all things spud-related.

His current day job is as a professor of contemporary art history at Hofstra University in Hempstead, New York. His passion is collecting, and making and staging exhibits of potato-themed art. Price was an early and enthusiastic presence on the web starting with “Think Potato” which featured links to potatoes in music, film and other media. His “Occupy Potato” Facebook page features his potato-themed art installations, collections and spud news.

Price pays attention to all things potato including songs on the radio. Here's his playlist which features images from his and The Potato Museum's collections.